Table of Contents

|

| Photograph by Zahidi Hamid (2015), permission granted. |

1. Overview

The Brown Boobook, also known as Brown Hawk-owl, is a resident breeder in most of tropical south Asia from India and Sri Lanka east to western Indonesia and south China. There are two subspecies of Brown Boobook in Singapore; Ninox scutulata scututala, which is a common resident breeder, and Ninox scutulata burmanica, which is a migrant. It is one of the most common resident owls in Singapore and can be found in habitats such as wooded parks and forests.

The Brown Boobook has similar plumage to several other owl species, in particular the Northern Boobook, N. japonica, which can also be found in Singapore as a rare migrant. Local birders may face difficulty trying to distinguish the Brown Boobook and Northern Boobook apart. For details on how to distinguish these two species apart, please refer to the section on 'Brown or Northern Boobook?' in the Table on Contents.

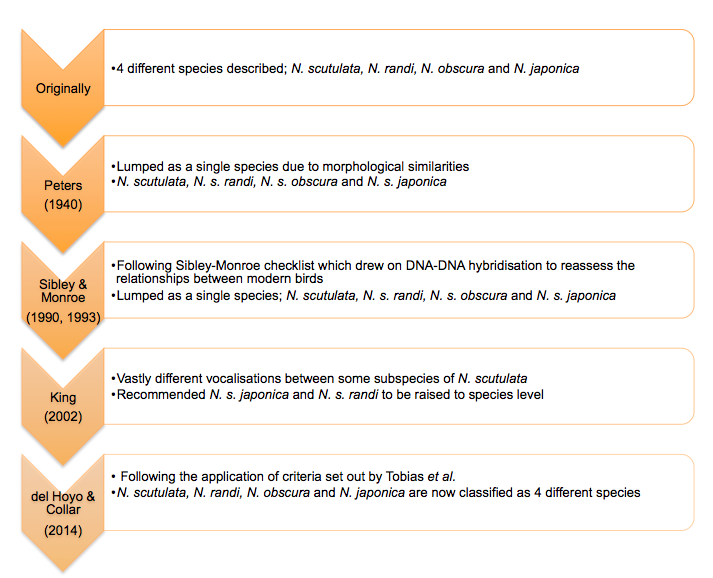

Several Ninox species were previously lumped as subspecies of N. scutulata, which went through a few taxonomic reclassifications[1] . Nocturnal birds with cryptic plumage can be easily overlooked as the same species when classified morphologically, thus several splits are found in the genus Ninox in recent genetics and bioacoustics research. To learn more about the taxonomy and phylogeny of this genus, please refer to the section on 'Taxonomy and Systematics'.

2. Description

2.1 Morphology

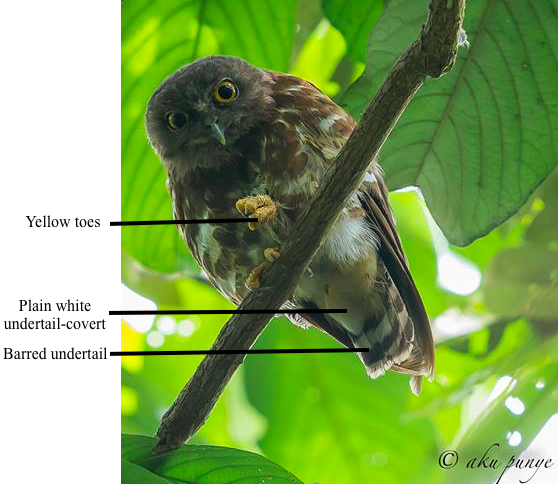

The Brown Boobook lacks a facial disc and possesses a long tail. Most owls have a concave facial disc which helps to direct sound to the ears for more acute hearing. It is a medium-sized owl that measures about 32cm in length, including its long barred tail. It has large, brilliant yellow eyes contrast with generally dark brown head, including face[2] . This owl has white patch above the bill, which is bluish-black. The upperparts are dark brown with white spots on the scapulars and inner secondaries. The undertail-covert is plain white, while tail is evenly dark-barred on both surfaces with four bars exposed dorsally [2]. The underpart plumage is whitish with brown streaks. Tarsi feathered, legs mottled dark brown and orange-buff, and toes yellow[3] . The males and females look alike.  |

| All photographs by Zahidi Hamid (2015) before edits |

|

| Juveniles (left and center). Adult feeding its young (right). All photographs by Vijay Anand Ismavel (2013), permission granted. |

2.2 Vocalisation

Due to their nocturnal behaviour and cryptic plumage, Brown Boobooks are more often heard than seen. Learning the call of the Brown Boobook can help to identify its presence when its call is heard. The Brown Boobook calls throughout most of the year, with the exception of June and July being its silent months. Callers are drawn quickly to playback in the daytime and after dark [2]. Their song is a hollow mellow double note call: whoo-wup. The second syllable is usually briefer and has a higher pitch than the first syllable.For more recordings of the Brown Boobook, please click here.

3. Diagnosis

3.1 Interspecific

N. scutulata, N. japonica, N. randi and N. obscura (del Hoyo and Collar 2014) were previously lumped as N. scutulata following Sibley and Monroe (1990, 1993)[4] . Though very similar-looking, they can be distinguished by slight morphological differences and distinct vocalisations.| Brown Boobook Ninox scutulata |

Northern Boobook Ninox japonica |

Chocolate Boobook Ninox randi |

Hume's Boobook Ninox obscura |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

3.2 Brown or Northern Boobook?

|

| Photograph of Brown Boobook by Johnny Wee (2012), permission granted. |

3.2.1 Significance

Correct identification of Brown Boobook from Northern Boobook is important as sighting records of Northern Boobook will allow better understanding of the migration pattern of this migrant species. In a recent genetics study by Sadanandan et al., it was found that of the three specimens that were collected in Singapore and presumed to be Brown Boobooks, one came out as Northern Boobook when their genetics were analysed.[12] This suggests that there may be an under-reporting of Northern Boobook's sightings in Singapore as they are easily confused to be the local Brown Boobook species.

3.2.2 Based on morphology

Although there seems to be a fair consistency in ventral patterning of the Brown Boobook and Northern Boobook (heart-shaped streaks on Brown Boobook and teardrop-shaped streaks on Northern Boobook) [5], some exceptions were observed. Individuals displaying ventral markings typical of Brown Boobooks have been photographed breeding across Japan (photo below), over 3000km away from the nearest confirmed breeding locality of Brown Boobooks, indicating that Northern Boobooks, especially from Japan, may display similar ventral markings [12]. In addition, ventral patterning may not be able to distinguish juveniles of both species apart due to the diffused markings on their belly (video below). As such, the range of variation in ventral patterning is not fully understood and may lead to some confusion with regards to distinguishing Brown Boobook and Northern Boobook in the field.

|

||

| Adult Northern Boobook showing heart-shaped streaks on breast and belly. Photograph by Joseph Morlan (2012), used by permission. |

Juvenile Brown Boobook displaying teardrop-shaped streaks on belly. |

|

3.2.3 Based on bioacoustics

Vocalisations serve as a useful and distinctive way to tell Brown Boobook and Northern Boobook apart. In fact, King (2002) proposed that N. scutulata, N. japonica and N. randi should be considered different species due to their vocalisation differences when the three species were still lumped as a single species [1].

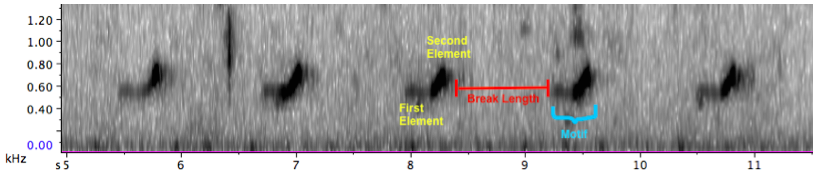

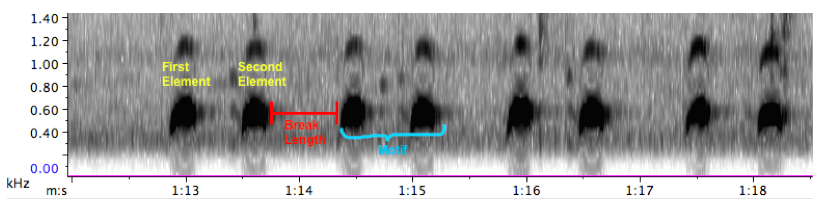

As mentioned earlier, the Brown Boobook's call is made up of a motif with two elements: whoo-wup. The Northern Boobook's call is also made up of a motif with two elements: ukh-ukh. However, the Brown Boobook's call can be distinguished from the Northern Boobook 's call by its second element, which has a higher pitch than the first element. Break length between each motif of a Brown Boobook's call is also longer (refer to sonograms below).

| Brown Boobook |

|

|

| Northern Boobook |

|

|

4. Biology

4.1 Behaviour

The Brown Boobook is nocturnal and normally roosts in the day to prevent being mobbed by other small birds.An interesting incident was observed when one playful Brown Boobook interrupted a badminton game in the evening. Click here for the original post.

|

|

| Photographs by Amit Thakurta (2009), permission granted. |

|

4.2 The Silent Hunter

Owls are capable of flying just inches away from their prey without being detected due to their specialised feathers which enable near-silent flight. Unlike most other birds which produce a 'gushing' sound when they fly as large areas of air turbulence build up, the comb-like leading edge of the owl’s primary wing feather (fimbriae) break up the flowing air into smaller, micro-turbulences. This effectively muffles the sound of the air rushing over the wing surface and allows the owl to fly silently. |

|

| Video by BBC showing the difference between a flying owl and other birds. |

Comb-like structure of the fimbriae.Photograph by Kersti Nebelsiek, licensed under Creative Commons. |

To maximise visibility, owls have very large eyes to see under low light conditions. They do not have eyeballs, instead their eyes are elongated tubes that are held in place by bony structures in the skull called sclerotic rings. Therefore, owls are unable to turn their eyes in the sockets and can only look straight ahead. Nevertheless, they are able to turn their head 270 degree to view in all directions. Owls are adapted to handle extreme head rotation. One of the major arteries leading to the brain passes through bony holes in the vertebrae, which are 10 times wider than the artery passing through. The extra space creates a set of air pockets that cushions the artery, thus allowing it to move around when twisted[13] .

| An owl turning its head 270 degree. |

4.2 Feeding

The Brown Boobook feeds mainly on large insects, such as beetles, grasshoppers and cicada. They also feed on small animals, such as bats, frogs, mice, lizards, and other small birds.Unlike other birds, owls do not have a crop which is a loose sac in the throat for storing of food for later consumption. Therefore, food is swallowed whole and passed directly into their digestive system. The gizzard serves as a filter and holds back insoluble content such as bones, fur, teeth and feathers. The content are then compressed into a pellet and regurgitated. For images of the owl pellets, click here.

4.3 Breeding and Nesting

|

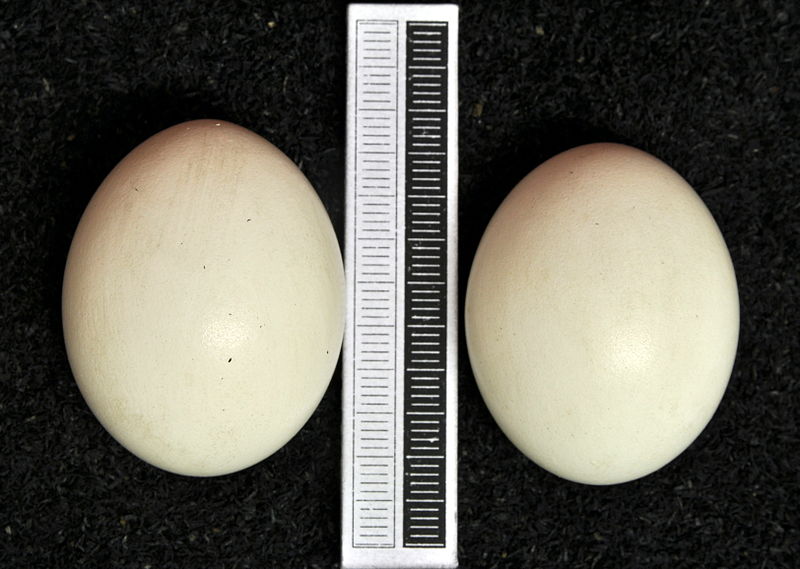

Laying and incubation occur from March to April in Sumatra, and March to July in India [23]. The Brown Boobook is very vocal during the breeding season, and can sing continuously for hours. They nest in any cavity or those in trees excavated by woodpeckers, and lay their eggs in a layer of natural debris at the bottom of the hole. Three to five eggs are laid in a tree hole. Eggs are white, roundish and have an average size of 36 x 31 mm. The female incubates the eggs alone, while the male provides her with food. Incubation lasts 25 or more days. Fledglings leave the nest hole 24-27 days after hatching, and are fed by both parents [2]. |

4.4 Moult

| The Brown Boobook usually moult once a year. Only single-locus moult of primaries were recorded, but pattern of replacement was uncertain[2]. When an owl hatches, it has no flight feathers and is covered with downy feathers that keep it warm. This down is gradually replaced with feathers after the juvenile has fledged. Feathers are shed and re-grown over the entire body in a regular pattern. Only a few of the primary or secondary flight feathers are shed at a time to minimise impact of the moult on the owl's flight and hunting skills. New feathers grow to replace the ones that have fallen out. The new feathers, known as pins, emerge from the skin tightly bound in a thin shaft of tissue. The shaft splits shortly after, allowing the new feather to unfurl and grow to its full size. |

|

4.5 Preening

Owls use their beak and talons to groom their feathers. The two outer talons act as the "feather combs", while the sharp medial edge of these talons enable them to clean their head.5. Ecology

5.1 Biodiversity indicator

|

| Brown Boobooks on Pulau Ubin. Photograph by Jacky Soh, permission pending. |

Owls can be used to estimate biodiversity because of several inherent traits:

- They are top predators which feed on a variety of prey.

- Many have large geographical ranges.

- They are sensitive to environmental changes and toxicants[14] . As they are top predators, toxicants found in the environment will accumulate in their body.

- Their undigested pellets can be studied to estimate population abundance among prey species[15] . It is a non-invasive method to study what prey species live in the area.

5.2 Pest control

They help to control rodent population and eat various pests that are harmful to crops. This is especially important to agrarian countries like India, where 60% of the population is dependent on agriculture.

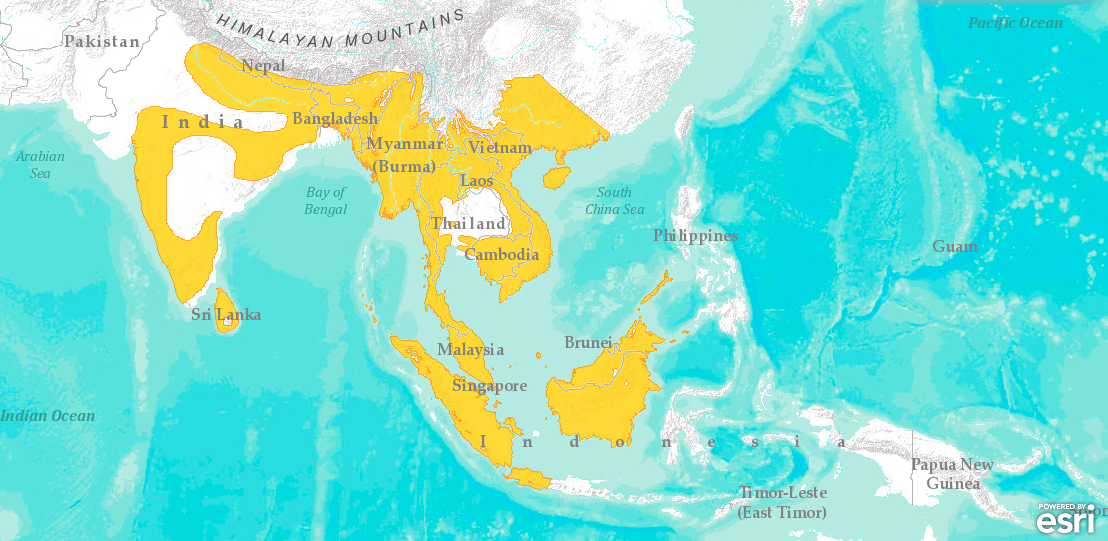

6. Distribution

This species occupies an extremely large range. It is native to Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam [4].

|

| Map of South Asia and Southeast Asia with Brown Boobook distribution indicated in orange (IUCN, 2015). |

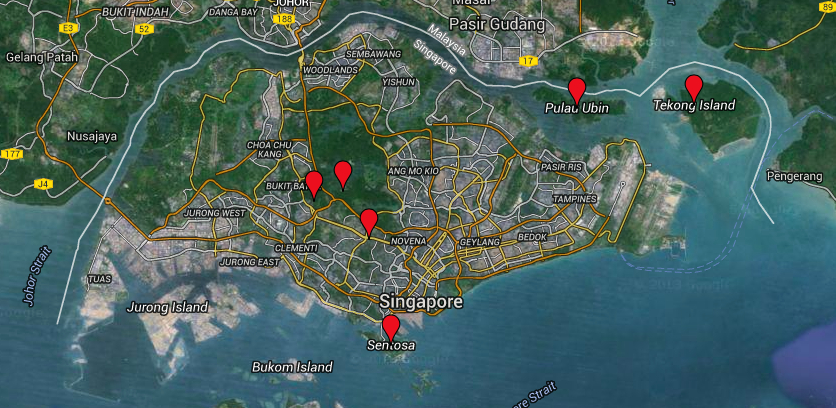

6.1 Distribution in Singapore

The Brown Boobook has been recorded in Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Pulau Tekong, Pulau Ubin, Sentosa and Singapore Botanic Gardens[16] . Their habitats include mangroves, forests, the forest edge, mature plantation, wooded suburban gardens[17] .

|

| Google Maps (2015) |

7. Conservation

7.1 Species Status

The Brown Boobook has an extremely large range, thus does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion. Though listed as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List, the population of Brown Boobook is probably declining due to loss of habitat through clearance of lowland rainforests.The Brown Boobook is considered common in Singapore as it is able to live in different habitats. However, deforestation and degradation of lowland tropical forests can potentially threaten the population of the Brown Boobook.

7.2 Owl Trade

|

|

|||||

| Photographs by Abrar Ahmed/TRAFFIC India, permission granted. For original post, please click here. |

||||||

Unfortunately, Harry Potter and his snowy owl, Hedwig, may be partly to blame for the increase in India's illegal owl trade. According to India's Environment and Forest Minister Jairam Ramesh, the country's population has become infatuated with owls as a result of the Harry Potter book series and films. In fact, many parents have bought wild owls from illegal bird traders to give them to their children as pets, according to Ramesh.

|

| Bird market in South Jakarta. Photograph is licensed under Creative Commons. |

“If anybody has been influenced by my books to think an owl would be happiest shut in a small cage and kept in a house, I would like to take this opportunity to say as forcefully as I can: You are wrong." ~J. K. Rowling

8. Taxonomy and Systematics

Nocturnal birds with cryptic plumage are commonly overlooked as the same species when classified based on morphology. As discussed earlier under 'Diagnosis', several owl species are morphologically very similar to N. scutulata and as a result lumped as subspecies of N. scutulata. However, these virtually indistinguishable owl taxa should be recognised as separate species as their vocalisations are very different, which is a character widely used in determining species limits in owls[18] . This section will discuss the taxonomy and phylogeny of N. scutulata, as well as highlight the taxonomic reclassification of N. scutulata and several other Ninox species.

8.1.1 Taxonomic Rank

A hierarchical summary of the taxa within which the Brown Boobook is placed is provided below:| Kingdom |

Animalia |

| Phylum |

Chordata |

| Class |

Aves |

| Order |

Strigiformes |

| Family |

Strigidae |

| Genus |

Ninox |

| Species |

N. scutulata (Raffles, 1822) |

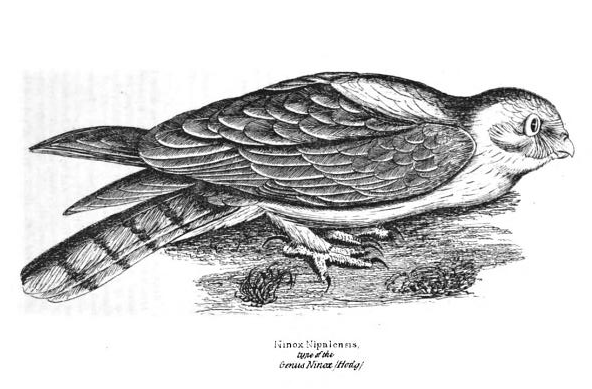

| Ninox? In Greek mythology, the Latin word, Nisus, is the king of Megara who turned into a hawk. The Latin word, noctua, refers to owl. Together, the genus name, Ninox, was derived by Hodgson in 1837 to describe the hawk-like appearance of Ninox nipalensis; junior synonym for N. scutulata lugubris (Tickell, 1833)[19] . scutulata? The species name, scutulata, is derived from the Latin word 'scutulatus' which means 'chequered'. |

|

|

| An illustration of Ninox nipalensis by Hogson[19]. |

||

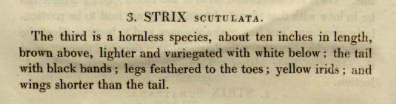

8.1.2 Original Description

The Brown Boobook was first described by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles with the protonym, Strix scutulata [20] .

The 'hornless' feature in the description refers to owls that do not have tufts of feathers on the tops of their heads, which could be otherwise observed in horned species such as the Buffy Fish Owl. The Brown Boobook was originally classified under the genus Strix, which was established by Linnaeus in 1758 to describe hornless owls. However, Strix is not the only genus that describes hornless owls and the Brown Boobook was later moved to Ninox.

8.1.3 Holotype

| Place of storage |

British Museum (Natural History) , presented by the Honorable East India Company Museum[21] |

| Register number |

1880.1.1.4760 |

| Location collected |

Sumatra |

| Age |

Adult |

| Condition |

Relaxed and mounted |

8.1.4 Taxanomic Splits

"Given that voice is the primary means of communication for nocturnal birds, selective pressure for intraspecific retention of stereotyped songs is likely to be strong, and nocturnal birds with different songs are therefore likely to represent different species. " ~ King, 2002

8.1.5 Subspecies

Subspecies is a taxonomic rank subordinate to species. A common way to decide if a subspecies is to be recognised by a taxonomist is that organisms belonging to different subspecies of the same species are capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offsprings, but they do not usually interbreed due to geographical isolation, sexual selection, or other factors.There are a total of nine subspecies recognised[23] .

| Subspecies |

Range |

Type specimen(s) |

| N. s. lugubris (Tickell, 1833) |

North and central India to western Assam |

Natural History Museum London (BMNH), Zoological Museum Hamburg (ZMH), Zoologische Sammlung des Bayerischen Staates, München, Germany (ZSBS)[24] . |

| N. s. hirsuta (Temminck, 1824) |

South India and Sri Lanka |

BMNH, Staatliches Museum für Tierkunde, Dresden, Germany (SMTD). |

| N. s. burmanica A. O. Hume, 1876 |

East Assam to south China, south to north Malay Peninsula and Indochina. |

BMNH, SMTD, ZMH, National Museum of Natural History, Washington (USNM) . |

| N. s. isolata E. C. S. Baker, 1926 |

Nicobar island |

BMNH (Holotype) Collection date: 19 March 1873 Catalog number: 1886.2.1.621[25] |

| N. s. rexpimenti Abdulali, 1979 |

Nicobar Island (Great Nicobar, Camorta, Trinkat) |

|

| N. s. palawanensis Ripley & Rabor, 1962 |

Palawan (southwest Philippines) |

Yale University Peabody Museum (Holotype) Collection date: 8 May 1962 Catalog number: YPM ORN 073202[26] |

| N. s. scutulata (Raffles, 1822) |

South Malay Peninsula, Riau Archipelago, Sumatra and Bangka |

BMNH (Holotype) |

| N. s. javanensis Stresemann, 1928 |

West Java |

Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin (Holotype) Catalog number: 131380 Click here to view type specimen[27] |

| N. s. borneensis (Bonaparte, 1850) |

Borneo and north Natuna Island |

BMNH (Holotype) |

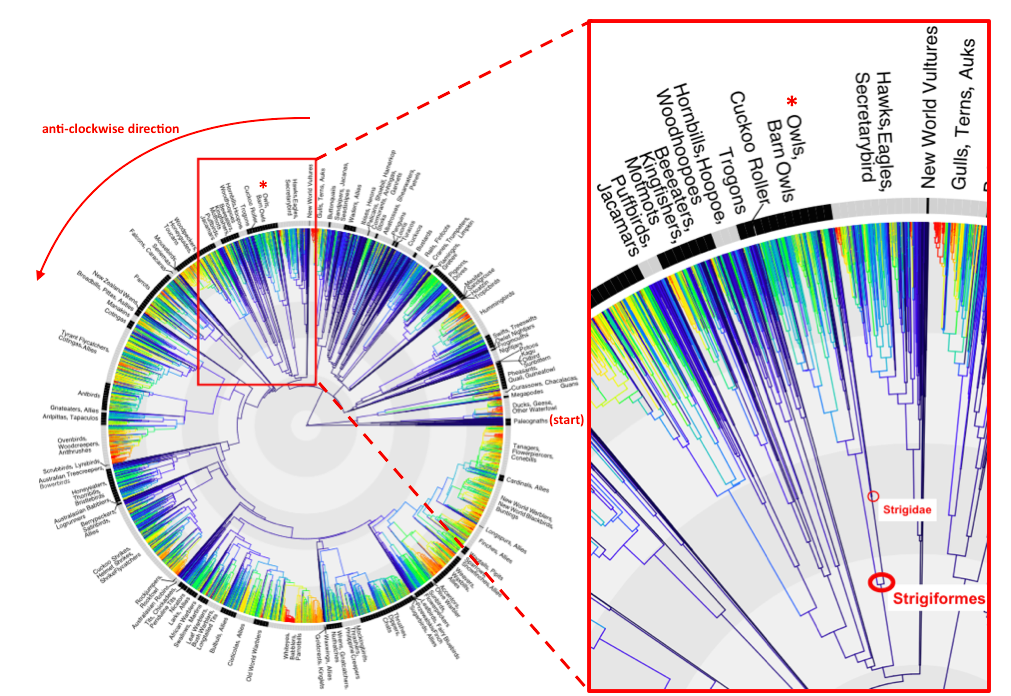

8.2 Phylogeny

Below is an illustration of the placement of owls on the avian tree of life. The branch length corresponds to evolutionary tree, starting with the oldest lineages of birds at the 3 o'clock position (labelled 'start') and subsequent avian evolution moving in the anti-clockwise direction. |

| The avian tree of life, with order Strigiformes and family Strigidae identified. |

Genbank provides barcode sequences of several genes of N. scutulata including CO1, RAG1, ND2, LDH and cytochrome b genes.

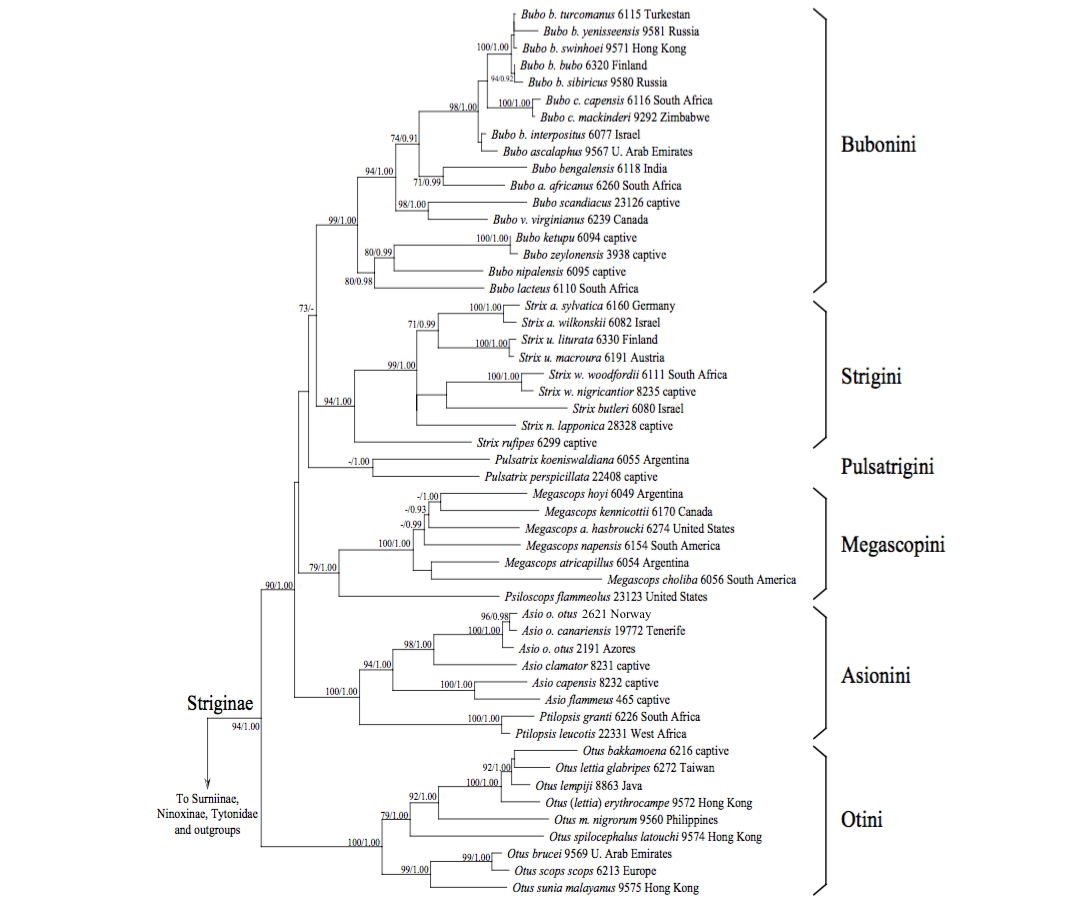

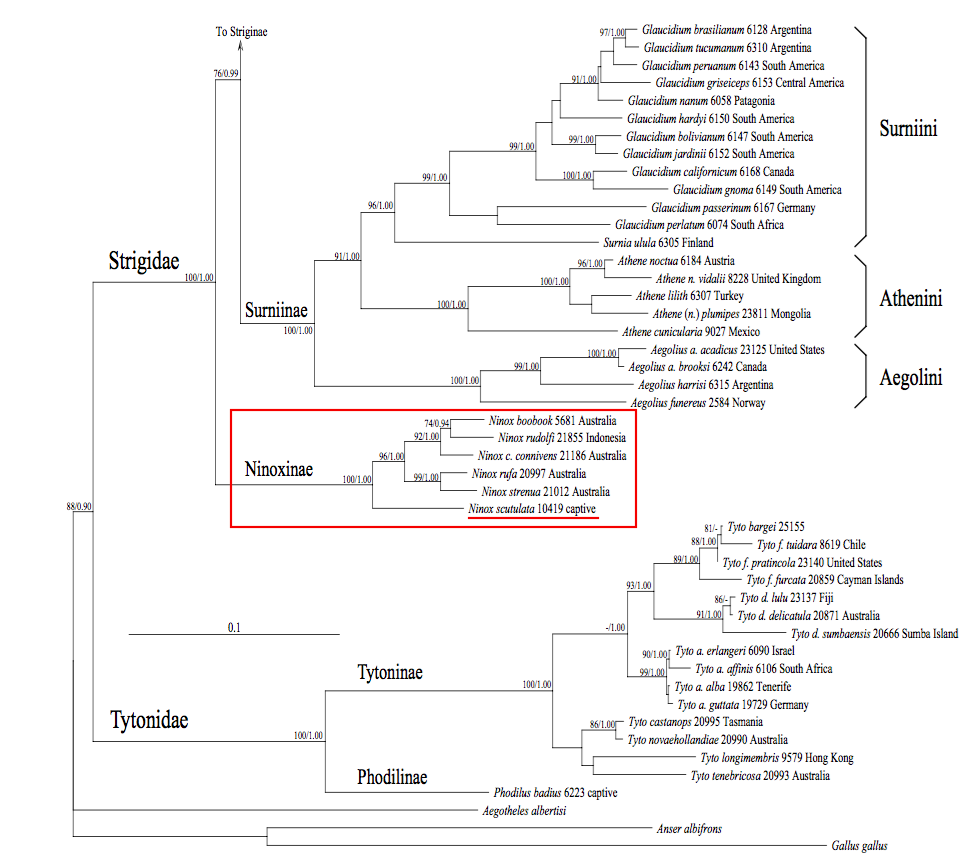

Below is the phylogenetic tree of Strigiformes based on RAG1 and cytochrome b genes, with the position of N. scutulata underlined in red.

|

| ML bootstrap phylogram of the generic relationships in owls based on a combined dataset of cytb and RAG-1 sequences (Wink et al., 2009) |

The genus Ninox forms a monophyletic group[29] . This genus proves to be problematic with several similar-looking taxa lumped together. Morphology is often cryptic and invariant in many owl species but the distinctive calls, which are inherited and not learned, are of considerable taxonomic value [28]. As of 2015, there are a total of 37 Ninox species recognised by Birdlife International, an increase from 21 in 2012[30] [31] . Further genetic and bioacoustics research may help in better understanding of the taxonomy and systematics of the owls in this genus, and more splits may be observed.

9. Fun Facts

|

|

10. References

King, B., 2002. Species Limits in the Brown Boobook Ninox Scutulata Complex. Bulletin of The British Ornithologists' Club, 122(4): 250-257.

Wells, D. W., 1999. The birds of the Thai-Malay Peninsular. Academic Press.

BirdLife International, 2014. Ninox scutulata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T22725643A40750333. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-2.RLTS.T22725643A40750333.en (accessed on 29 Sep 2015).

Sadanandan, K. R., D. J. X. Tan, K. Schjølberg, P. D. Round & F. E. Rheindt. (in press). DNA reveals long-distance partial migratory behavior in a cryptic owl lineage. Journal of avian research.

"Twist and hoot: secret of owls' neck rotation revealed," by Campbell, C. TIME, 4 Feb 2013. URL: http://newsfeed.time.com/2013/02/04/twist-and-hoot-secret-of-owls-neck-rotation-revealed/ (accessed on 27 Nov 2015).

Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, 2015. Ninox scutulata. URL: http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/852 (accessed on 29 Sep 2015).

Dunn, J. L. & D. Gibson, 2014. Split Ninox japonica from Brown Hawk-Owl Ninox scutulata and adopt the English name Northern Boobook. AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America.

Morris, J. C. (Ed.), 1873. The Journal [afterw.] The Madras journal of literature and science. Journal of literature and science, 5: 23-25.

Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, 1822. Linnean Society of London, 13: 280.

Warren, R. L. M., 1966. Type-specimens of birds in the British Museum (Natural History). Vol. 1 Non-passerines. The British Museum (Natural History).

Tobias, J. A., N. Seddon, C. N. Spottiswoode, J. D. Pilgrim, L. D. C. Fishpool & N. J. Collar, 2010. Quantitative criteria for species delimitation. Ibis, 152: 724-746.

Olsen, P.D., E. D. Juana & J. S. Marks, 2015. Brown Boobook (Ninox scutulata). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. URL: http://www.hbw.com/node/55105 (accessed on 3 Nov 2015).

Weick, F., 2006. Owls (Strigiformes): annotated and illustrated checklist. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Natural History Museum, 2014. Dataset: Collection specimens. URL: http://data.nhm.ac.uk/specimen/8f6091f1-d9c6-43a8-a0de-502c1d0be7ee (accessed on 29 Sep 2015).

Global Biodiversity Information Facility. URL: http://www.gbif.org/occurrence/1039647725 (accessed on 3 Nov 2015).

SysTax - Zoological Collections. URL: http://www.gbif.org/occurrence/1038141942 (accessed on 29 Sep 2015).

Wink, M., A.-A. El-Sayed, H. Sauer-Gürth & J. Gonzalez, 2009. Molecular phylogeny of owls (Strigiformes) inferred from DNA sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b and the nuclear RAG-1 gene. ARDEA, 97: 581-591.

Wink, M., H. Sauer-Gürth & M. Fuchs, 2004. Phylogenetic Relationships in Owls based on nucleotide sequences of mitochondrial and nuclear marker genes. In: Chancellor, R. D. & B.-U. Meyburg (eds.). Raptor Worldwide, 517-526.